Heart warming Article from Catholic Answers website:) Summer*

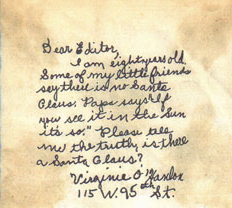

Once upon a time, a long time ago by journalistic standards, a little girl wrote a letter to The Sun, a New York City newspaper. Little Virginia O'Hanlon, eight years old, had a very important question to ask:

Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus. Papa says, "If you see it in The Sun it's so." Please tell me the truth: Is there a Santa Claus?

The editorial response, published by The Sun, written by Francis P. Church, begins:

The silent actor in this drama was Virginia's father, Dr. Philip O'Hanlon, who apparently chose not to answer his daughter's question and punted it to a newspaper. We have no record of why he did so. Perhaps he did not want to be the one to dash his daughter's belief in Santa Claus and thought it better for the newspaper to tell her the bad news. Or, because he was a medical doctor and therefore a scientist, perhaps Dr. O'Hanlon decided that Virginia was old enough to begin to seek answers to life's questions from the wider world beyond the circle of her family.Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age. They do not believe except they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men's or children's, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

In any case, Dr. O'Hanlon's dilemma, unlike his daughter's, never received an answer. To this day parents wonder what to tell their children about Santa Claus. The apologists at Catholic Answers receive questions on this topic every year about this time. Here is one example:

The Catechism of the Catholic Church [CCC 2485] is very clear that we shouldn't lie for any reason. How then can we justify lying to children about Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, and the Tooth Fairy, by telling kids they are real when we know they aren't?Perhaps you have noticed from this question that it is now the parents, not the children, who are victims of what Francis Church called "the skepticism of a skeptical age." Staring at black and white, they see no gray. Something is either factually true or it is a "deception." Frankly, this is an impoverished understanding of the nature of language, of thought, and of truth.

Let's backtrack for a moment and look at some history.

The stories commonly told today about Santa Claus are based on legends surrounding the life of a real person. St. Nicholas of Myra was a fourth-century Catholic bishop in Turkey. He participated in the First Council of Nicaea—where he was famously purported to have slugged the heretic Arius for denying Christ's divinity—and has been considered a patron of children for his generosity to them during his lifetime.

For example, he is said to have provided dowries for three girls who would have been sold into slavery if they could not make good marriages. Over the centuries, the legends of St. Nicholas's life have been supplemented with Northern European myths, eventually culminating in the children's story A Visit from St. Nicholas by Clement C. Moore, which imagined St. Nicholas as a "right jolly old elf," traveling the world on Christmas Eve in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, distributing gifts to children.

(Nota bene: It is worth considering that the name "Santa Claus" is not merely an imaginary moniker arbitrarily affixed to a jolly elf wearing red. The name is an Americanization of the Dutch Sinterklaas, which translates to "Saint Nicholas.")The parental dilemma arises when children find out that their parents are the ones who are providing the Christmas gifts, Easter candy, and tooth money. In my experience, parents tend to worry too much about how their children will receive this news. Many children through many generations simply accept this information as a part of growing up, and, in fact, some will "collude" with parents to keep the myth going by not letting their parents in on the fact that they know The Truth About Santa Claus. One reason may be to continue getting loot, but another reason may be to avoid spoiling their parents' or younger siblings' fun.

There may be children, though, who are sensitive to issues of truth versus lying and who may sincerely wonder if their parents have "lied" to them about Santa Claus. One way to answer this concern might be to explain the context of storytelling and myth-making, perhaps pointing out to the child that Let's Pretend is a game for people of all ages.

But is it "lying" to allow children to believe a myth? In my opinion, that is a misunderstanding of the nature of myth-making.

Cultures create and foster myths as a means of understanding the world around them. In the absence of science, the ancients needed ways to explain the natural phenomena, such as the movements of the sun, that they could not examine directly. Modern people tend to smile with condescension at the thought of ancient Greeks believing that the god Helios drove his golden chariot across the sky every day. They do not consider that perhaps the ancients knew as well as they do that this is not factually true but is merely a story that taught an important truth: There are reasons why we have periods of light and darkness, even if the ancient Greeks could not yet explain those reasons scientifically.

We may now have ways to scientifically explain natural phenomena, but we have not lost the need for story or for myth. And the ones who sometimes learn best through stories are children.

So, what can children learn about their world through belief in Santa Claus?

Well, for one thing they can learn that good behavior is rewarded and bad behavior is punished, not just because their parents say so, but because there is something larger than their parents that requires us to act rightly. The other day while my sister was driving with her children, another driver blew through a red light. My older niece, age ten, wanted to report the man to the police. My younger niece, age four, agreed with the idea but offered an additional suggestion: "And Santa Claus too! He'll put the man on the bad list!"

Children can also can learn from the Santa Claus legend that we are part of a larger universe, and that we are watched over and cared for by good spirits whom we cannot yet know empirically. This can be considered groundwork for introduction to the communion of saints. And, because Santa Claus is based on a real person, they need never stop believing in him; they need only mature in understanding of how St. Nicholas answers their requests.

Does this mean that Catholic parents must allow their children to believe in Santa Claus? Of course not. If a parent does not feel comfortable taking this approach to Santa Claus (or the Easter Bunny, or the Tooth Fairy) the parent is free to leave out such stories from his child's formation. I do think that Catholic parents should teach their children not to spoil the innocent fun of other children by telling those children that such characters are Not Real.

Virginia O'Hanlon eventually did learn The Truth About Santa Claus, of course. How did she turn out once she discovered The Truth? She grew up to be an educator. Throughout her life O'Hanlon continued to foster belief in Santa Claus by sending copies of Francis Church's editorial to the admirers who sent her letters. According to Wikipedia, O'Hanlon "credited [the editorial] with shaping the direction of her life quite positively."

No Santa Claus! Thank God, he lives, and he lives forever. A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, ten times ten thousand years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood (Francis P. Church).

Yay! I did not destroy my children's trust by lying to them! I taught them bigger, deeper mysteries of the Faith and had a ton of fun doing it!

ReplyDelete